This is the story of Thomas Hudner.

Between November 27th, and December 13th, 1950, 30,000 United Nations troops fought a desperate defense while surrounded by 120,000 Chinese soldiers. The U.N. troops were part of a task force given the difficult job of securing South Korea’s freedom and independence from her Communist counterpart to the north. The fighting was marked with intense cold, snow, and horror.

But over the heads of the infantry and tankers on the ground, the United States had unleashed one of the largest collections of airpower since World War 2. The 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, along with the five aircraft carriers of US Navy Task Force 77 flew 260 sorties daily, with the ground troops being supplied by US Air Force planes from Japan. While these planes were usually able to fly with impunity, one, flown by the first African-American fighter pilot in the United States Navy, Jesse L. Brown, was shot down on December 4th, 1950.

Brown was part of a flight of six aircraft from USS Leyte, an aircraft carrier from Task Force 77. He and his squadron mates had already flown numerous sorties over Korea and were experienced combat pilots.

Taking off at 1338 hours, the flight went out in search of any enemy activity near the west of the Chosin Reservoir, where most of the UN troops were trapped. Their orders were simple, to search out and destroy the enemy, and report any large troop formations they encountered. But their flight that day was uneventful.

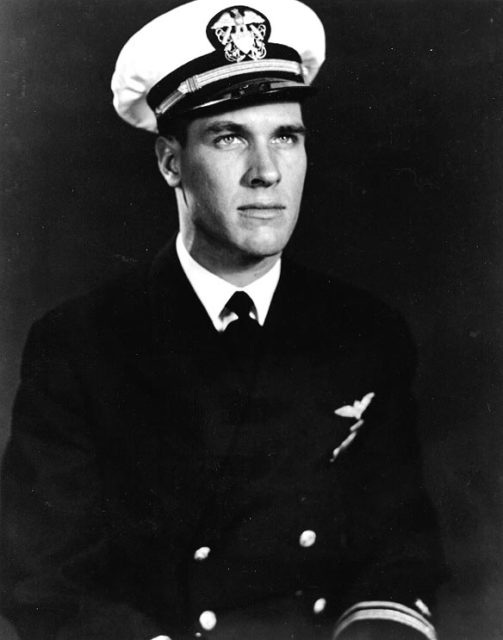

Despite flying only 700 feet above the ground, the six F4U Corsairs were unable to locate any enemy troops. They turned around and headed back east to rejoin their carrier. It was around this time that Jesse Brown’s wingman, Lieutenant Junior Grade Thomas Hudner, noticed a stream of fuel coming from Brown’s wing. Their day had just gotten a lot worse.

While the flight hadn’t encountered any large troop formations, that leak didn’t come out of nowhere. It is likely that Chinese infantry had buried themselves in a snow bank, and aiming their rifles skyward, formed a small anti-aircraft platoon. Considering the slow speed and low altitude of the Corsair flight, this is the most likely explanation.

Regardless of how he was hit, Brown started to lose control of his Corsair, and his oil pressure dropped drastically. He knew that the plane wouldn’t last long, so he began looking for a usable crash location. Jettisoning his external fuel tanks and air to ground rockets, he selected a large snow-filled plain on the side of a mountain. He brought his plane down low and braced for a wheels-up landing. Meanwhile, his wingman, Hudner, could do nothing but watch as his close friend careened towards a frozen world full of enemy combatants.

When Brown touched down, his entire aircraft was torn apart, leaving him still trapped in the cockpit. The rest of the flight continued circling overhead, keeping an eye out for any enemy activity. His mates assumed Brown was dead until they saw him open his canopy and start waving to them. But something was wrong, he wasn’t getting out of the aircraft. To make matters worse, a fire had broken out in the main fuel tanks, and they could see the column of smoke rising from the fuselage. They radioed for assistance and received word that a rescue helicopter was on its way.

But Thomas Hudner knew that Brown might not be able to wait for the helicopter to make it. His friend was trapped in enemy territory in a burning plane, and he had to do something to help. Acting on instinct Hudner dropped his tanks and rockets and started to slow down in preparation for a wheels-up landing.

Hudner intentionally crashed his plane near Brown’s and rushed to his friend’s aid. At first, he tried to pull him from the twisted metal wreckage. But the cockpit fuselage had buckled so severely in the impact that Brown’s leg was intertwined with the plane. Focusing instead on fighting the fire, Hudner started packing as much snow as he could around the aircraft. This slowed the fire, but didn’t help Brown’s state, who was already slipping into and out of consciousness. Finally, after about fifteen minutes, the rescue helicopter arrived. The pilot and Hudner at first attempted an amputation of Brown’s trapped leg, but the light was fading fast, and the helicopter couldn’t operate in the dark. Finally, Brown slipped out of consciousness, after saying to Hudner “Tell Daisy I love her.” Hudner had to pull himself away, and get back to safety on board the helicopter.

Back onboard the Leyte, Hudner begged for permission to return to the site and retrieve Brown’s body, but his request was denied. The command knew that a downed plane was an easy ambush point for the enemy, who would love the opportunity to destroy an American helicopter and kill its pilot. But his superiors also knew that they couldn’t let the enemy deface or mistreat Brown’s body, or get access to the aircraft. They decided on a cremation by napalm.

On December 6th, 1950, a flight of Corsairs from the Leyte dropped napalm on Brown’s crash site, while reciting the Lord’s Prayer out of respect. They noted that the plane appeared undisturbed, save Brown’s winter clothes missing. This is understandable, as the Chinese troops in the region were poorly equipped for the Korean winter, and wouldn’t have passed up the opportunity to get a warm leather flight jacket.

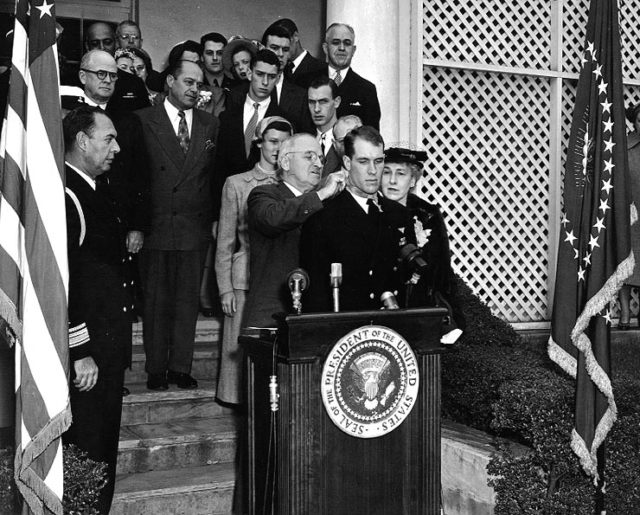

For his actions on the 4th of December, Thomas Hudner was awarded the Medal of Honor. His bravery, and his willingness to risk his own life to save a fellow pilot exemplified the comradery and co-reliance which are cornerstones of military values. But there was also a backlash against Hudner, and many said he needlessly wasted an aircraft and endangered a helicopter and its pilot. Hudner’s response to this criticism has always been to explain that he is not a hero, but made a spur of the moment decision to try and save a friend.